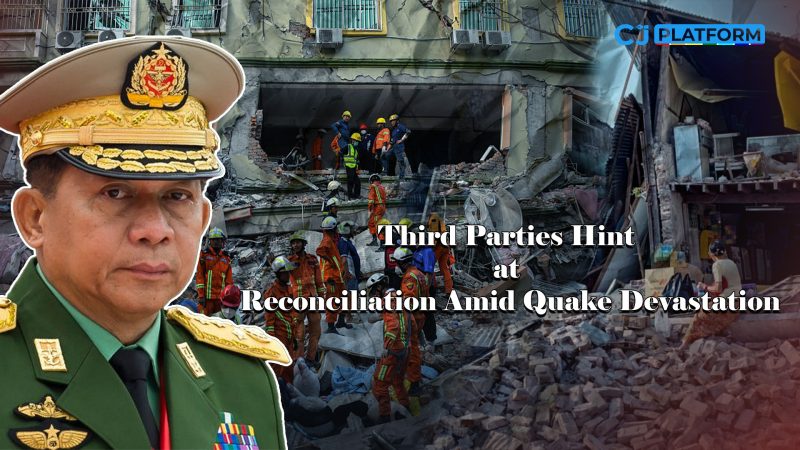

Third Parties Hint at Reconciliation Amid Quake Devastation

Whenever the military junta calls for elections, groups identifying themselves as “Third Parties” often seize the moment to promote so-called national reconciliation.

Following the junta’s forced ratification of the 2008 Constitution, some members of these Third Parties began voicing appeals—often discordant and out of touch—for reconciliation. Their version of “national reconciliation” amounts to an unconditional surrender by pro-democracy forces, encouraging them to participate in elections orchestrated by the military regime, such as those held in 2010.

These Third Parties have consistently called on pro-democratic groups to reduce tensions and join the military’s political roadmap. Yet, despite their appeals, the junta passed laws that effectively barred the National League for Democracy (NLD) from participating in the 2010 elections. The regime’s Political Party Registration Law explicitly disqualified anyone serving a prison sentence or appealing a conviction from forming or joining a political party—an exclusion clearly aimed at preventing many NLD members, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, from participating. The discriminatory intent of this restriction was obvious to the people of Myanmar.

While Third Parties preached reconciliation, then-junta leader Than Shwe sought to eliminate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD from Myanmar’s political arena altogether.

It wasn’t until the presidency of Thein Sein, a former general appointed by Than Shwe, that the NLD was allowed to contest the 2012 by-elections. This move was widely seen as an attempt to gain international legitimacy for the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP).

Thein Sein underestimated the public’s support for the National League for Democracy (NLD), believing that his military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) would easily win the 2015 general election. Under the 2008 Constitution, which reserves 25 percent of parliamentary seats for the military, only the USDP was seen as capable of forming a government. The military and its allies assumed that, following the election, the USDP would secure a majority and allow them to continue governing. Thein Sein and his circle simply envisioned the NLD as a mere opposition party in parliament.

However, when the 2015 election results were announced, the USDP suffered a landslide defeat, making it impossible for them to form a government. The Election Commission that oversaw the vote was composed of former military generals aligned with the USDP, making any allegations of vote rigging against the NLD baseless. Ultimately, they were forced to hand over power to the NLD.

During the NLD’s time in government, the military, USDP, and their affiliates—including the extremist nationalist group Ma Ba Tha—carried out coordinated, systematic efforts to obstruct and discredit the NLD administration. Their strategy was to undermine the NLD’s ability to govern and to position themselves for a return to power in the 2020 election.

However, the USDP again suffered a humiliating defeat in 2020. Realizing that they could no longer regain power through democratic elections, the military concluded that their only remaining path was to return to their traditional method—seizing power by force. This led to the military coup in 2021.

Min Aung Hlaing believed that, as in the previous two military coups, the people would surrender once the army began shooting and killing protesters. However, he was met with the determined resistance of an entire nation. The Operation 1027 offensive dealt a major blow to the regime, and 2024 marked a year of serious setbacks for the junta. Still, the military continues to rely heavily—and traditionally—on the support of Russia and China.

Despite these challenges, Min Aung Hlaing remains determined. With unwavering resolve, he is pushing ahead with plans to hold elections, aiming to cement his grip on power by becoming an “elected” president. His goal is to secure eternal control through a vote conducted on his terms.

When Min Aung Hlaing announced the election date while visiting Belarus, parties affiliated with the military council expressed great excitement, hoping for a “runt’s share” of power. So-called third-party groups, however, avoided voicing support for the election under the pretext of reconciliation, knowing that they would face sharp public criticism.

Instead, these groups repackaged their call for reconciliation in the context of the devastating earthquake. On March 29, just one day after the quake, U Hla Maung Shwe posted on his Facebook page under the title: “Thoughts Emerged 22 Hours After the Earthquake.” Despite never having made a meaningful mark in Myanmar’s political arena, U Hla Maung Shwe first surfaced as a “third-party” figure before 2010 and attempted to organize so-called peace talks in 2011. When the military launched its failed coup, he didn’t even join the people in protest with a symbolic three-finger salute.

With such a history, U Hla Maung Shwe’s “thoughts” after the earthquake seem less like reflection and more like an opportunistic echo of old tactics.

When Cyclone Nargis struck in 2008, the military junta initially refused international aid, only later allowing limited assistance. In contrast, following the recent earthquake, international aid arrived promptly. Yet U Hla Maung Shwe, rather than immediately calling for more international assistance, began his public response by praising Min Aung Hlaing, calling him more intelligent than his predecessor, Than Shwe.

He then noted that representatives from at least eight countries had asked him whether Myanmar could pursue national reconciliation in the wake of the disaster.

“I don’t know yet whether the key stakeholders can actually make it happen,” he said. “If they can do it, that would be good. There are many stakeholders involved. If the conflict can stop, it would be good. If it can be reduced, that would also be good. I don’t know who can do it. But at least we, the common people, can begin doing what we can.”

U Hla Maung Shwe’s appeal to the public was framed as a moral message: “No one should violate the law even if others have no rules or discipline. We should make ourselves good, regardless of whether others are good or bad—not respond with good for good and bad for bad.”

His message, however, implies a problematic tolerance. It suggests that when the military junta kills civilians, destroys property, or loots, the people should remain law-abiding and silent. In essence, he calls for patience and restraint from citizens, while excusing the junta’s violence and lawlessness. He concludes that national reconciliation requires courage and maturity from the people—without mentioning accountability or justice.

In a country prone to natural disasters, military generals are obsessed with power yet utterly unprepared to respond to emergencies. When a devastating earthquake strikes, their only response is to call for international aid—revealing a complete lack of planning or capacity. While ordinary citizens are left to face the destruction and trauma alone, struggling through tears and loss, U Hla Maung Shwe oddly urges the people to “remain good” even in the face of the military council’s brutality.

A closer review of statements made by third-party actors reveals a troubling pattern: they shift blame onto the people and the revolutionary forces while pretending not to see the junta’s actions. Instead of holding the military accountable, they preach tolerance in the face of its misconduct. This raises an important question—should elections conducted by such a regime be legitimized under the banner of “reconciliation”?

Currently, the military council shows no intention of genuine reconciliation. It continues bombing numerous regions even after announcing a ceasefire. Yet the so-called third parties remain silent on these attacks. When Min Aung Hlaing publicly declared that the earthquake would not delay the election—despite the widespread suffering of the people—these third-party groups dared not voice any criticism.

After the recent earthquake, third-party groups took advantage of the situation to raise their voices. While they have attempted—unsuccessfully—to persuade revolutionary forces to focus on national reconciliation, curb extremism, and support the military council’s planned elections, their efforts have not gained traction.